A mother's grief: not enough for Picasso?

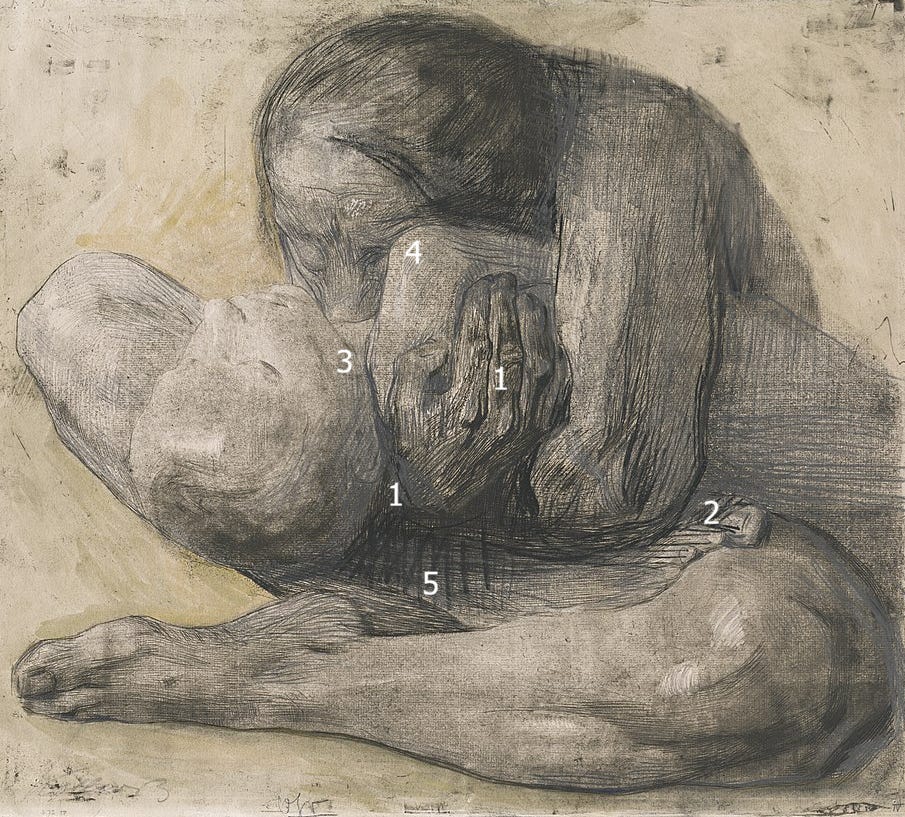

In jazzing up Kollwitz's 'Mother With A Dead Child' for 'Guernica', Picasso imposes both his character and his graphic language.

Seeing Picasso’s Guernica in the Reina Sofía in Madrid set me thinking.

Picasso is celebrated for how profoundly he conveys emotion. Two of his works from 1937 feature female suffering and grief in a way that I find particularly striking.

Considering these works in the context of the lives of the women involved gives the lie to Picasso’s apparent empathy.

His paintings reveal nothing about genuine female suffering and grief, and plenty about the attitude to women that he displayed in words, life, and art.

Guernica

In 1937, Picasso was commissioned by the Spanish Republican government to produce a large mural for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris International Exposition. While Picasso was contemplating design ideas in Paris, the strategic Basque town of Guernica was attacked by the German Nazis and Italian Fascist Air Force. Based on an eye-witness account of the bombing, Picasso decided to use this event as the subject of the commission.

Both Picasso (in Paris) and Käthe Kollwitz (in Berlin) had anti-war protest as a key feature of their work.

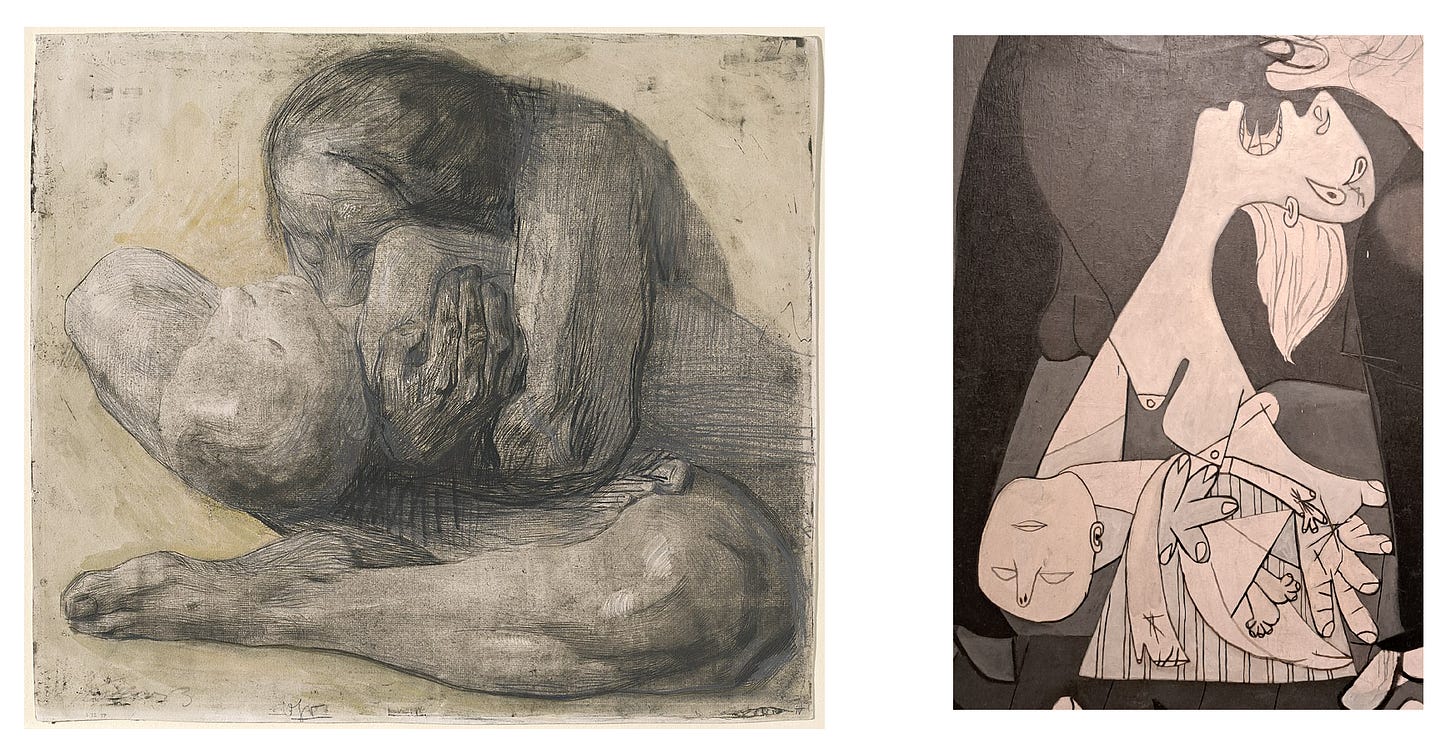

Kollwitz started this etching around 1903. It is in the Pietà tradition, based on a self portrait modelled with her 7 year old son in front of a mirror. That son Peter died aged 18 on the battlefield in Flanders in World War I in 1914. A few early-state proofs (when the etching plate hadn’t been fully completed) exist, but the definitive edition of 50 impressions (see image above) was printed and signed by the artist in 1918. Further editions were printed up to 1941, which implies it was well received, and distributed, particularly within the international anti-war artistic community of which Picasso was a member.

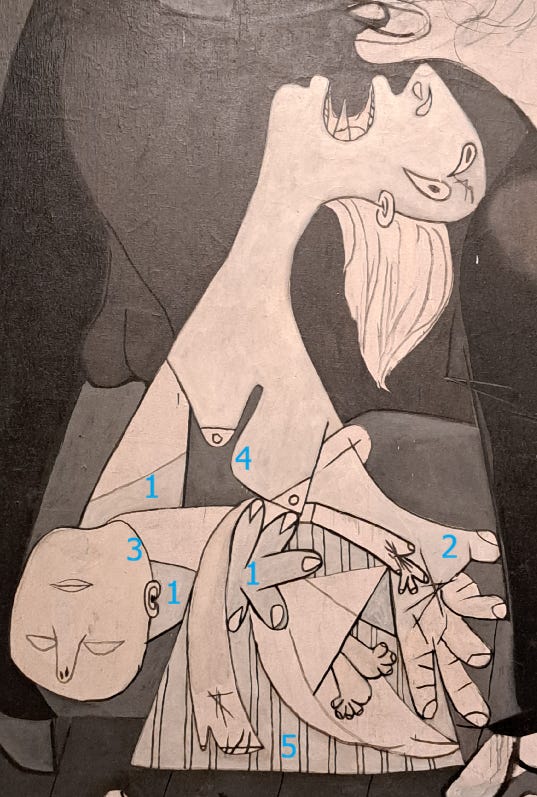

I am very familiar with Kollwitz’s image, having featured it in my own painting:

On seeing Guernica, I was immediately struck by his brilliant sampling and recontextualising of Kollwitz’ Woman With A Dead Child. It was like seeing an old friend.

Picasso was not in the habit of acknowledging references, but I would argue that the similarities listed below contradict all reasonable doubt that his image is derived from that of Kollwitz. This is also an insight into how Picasso edited and translated visual information into his idiosyncratic graphic style:

1 The position of her arm and hand, scooped under the neck.

2 The position of her thumb in Picasso’s version, reminiscent of her toe in the Kollwitz

3 The orientation of the whole image, illustrated by the position of the child’s head, with a section of his neck visible.

4 The incongruous corner of her breast in Picasso’s version, echoing the child’s shoulder in the Kollwitz

5 The heavy vertical hatching in the Kollwitz, where Picasso has put a vertical stripe pattern.

Although I haven’t seen anyone else make these connections explicitly, and there are other inputs at play, it isn’t particularly contentious that he referenced Kollwitz’s imagery here.

I fully support (and do myself) the sampling or quoting of the work of other artists. These are my objections to Picasso’s approach:

The borrowed image embeds authentic mother’s grief (Kollwitz’ personal experience of her husband’s patients, and her own loss) into Picasso’s anti-war painting. Perhaps her intimately crouching pose was not dramatic enough to Picasso’s eye. Along with other changes, he raised the woman’s head into a wailing gesture, thereby also revealing her breasts. So in a festival of crassness, Picasso took Kollwitz’s image, layered hysteria over her grief, and added boobs.

Anyone creative builds on, and contributes to, the immemorial communal pool of ideas. Seeing Guernica in the Reina Sofía museum, Kollwitz’s specific details and rhythms jumped out at me, thanks to hours spent copying her etching in my The Raft Of The Medusa. When quoting the work of others there is a moral obligation to give credit. There is no record of Picasso doing this.

In Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (1999), Griselda Pollock argues that the Western art historical canon has systematically marginalized women’s contributions, resulting not only in the absence of female artists’ names but also in the erasure of their ideas, practices, and ways of thinking about art. Art historians who water down attribution to Kollwitz with tepid phrases like “inspired by” deny Picasso’s derivative use of her authentic original motif, and boost his legacy at the expense of hers.

Weeping Woman

Picasso used Dora Marr as a model for this series of portraits. He is quoted as saying “a portrait shows what the artist knows or feels about the subject, not what the subject thinks of themselves”.

His relationship with Maar was characteristically abusive. When they met, he was separated from (and for financial reasons refusing to grant a divorce to) Olga Khokhlova. His mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter (27 years his junior) had just given birth to their child.

This was at the early stage of their relationship, during which time Maar modelled for him extensively. She sourced him a studio, educated him politically, and documented his progress on Guernica.

Picasso did lots of self-portraits. Many artists turn to self portraiture to depict themselves in heightened emotional states. A really interesting sub-oeuvre of self portraiture, this can be as a technical exercise, or to process actual feelings. It is often reflected that by using yourself as the model, you don’t need to give any thought to the model’s feelings about how they are represented.

It is a totally different proposition to superimpose despair onto the portrayal of a third party, let alone an intimate partner.

Positioned as representing the suffering of women, this series is chillingly prophetic of the control and suffering he would mete out to Maar over the following years. Picasso repeatedly portrayed her in distress, to the extent that eventually being “Picasso’s weeping woman” eclipsed Maar’s public reputation and career as a photographer.

Self portrait of photographer-artist Dora Maar “All portraits of me are lies. They’re Picasso’s.”

Conclusion

I can find no record of Picasso acknowledging Kollwitz’s etching. Although she was alive, productive, and critically acclaimed in 1937 when he painted Guernica, Picasso’s success, reach, and influence were of a different order to hers.

On a superficial level I don’t have much difficulty separating the personal life/character of an artist from their art, where they are essentially discrete. I appreciate some of Picasso’s work, and admire his boundless drive to create and innovate. However his character is integral to the choices described in The Weeping Woman, Guernica, and many of his other works.

Given that Guernica was exhibited at the Paris Exposition, then toured before being taken to Madrid, Kollwitz is likely to have known of the celebrated public commission, and would have recognised her vignette within it. If so, I wonder how she felt about it. Perhaps she would have felt they just had a common goal. Perhaps like Picasso she was busy working. Either way, his silence deprived her of visibility.

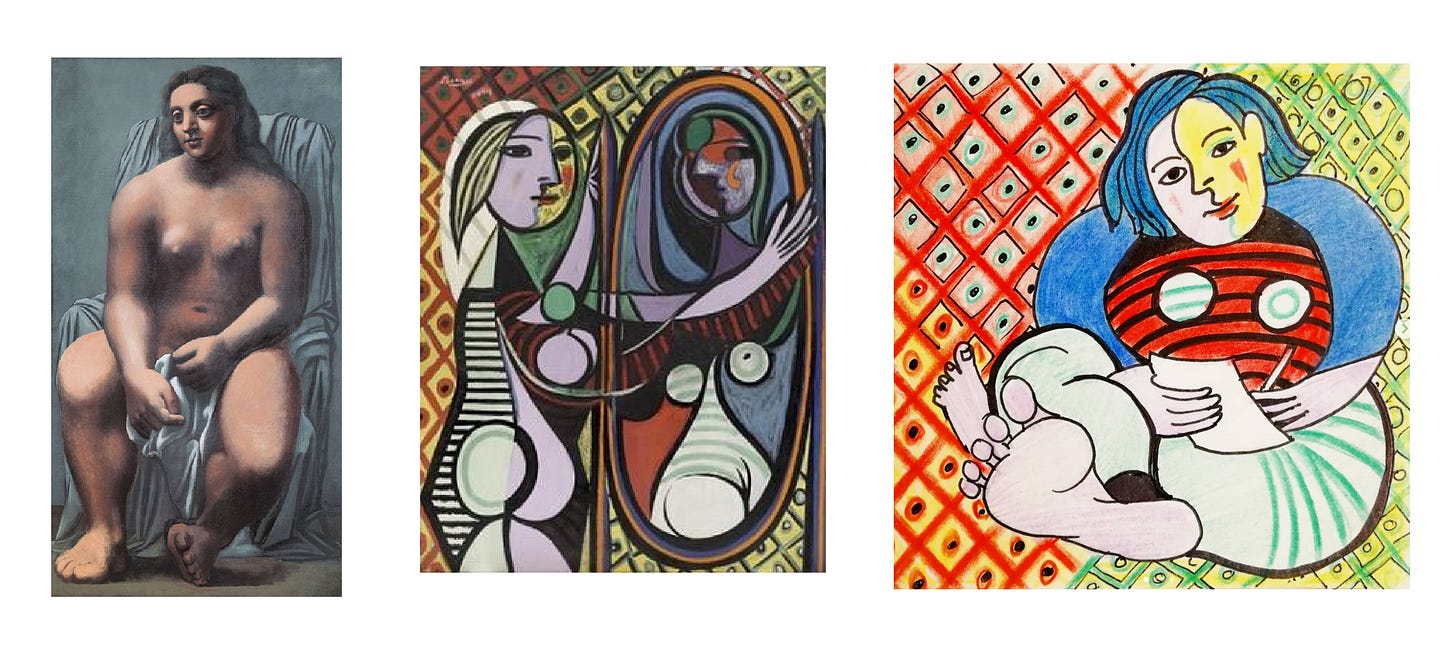

And as a woman artist, I can attest that visibility is very hard to come by, even though there has been progress since 1930s Europe. In 2020 I tried blue hair, sat in front of a mirror, and made a self portrait in the style of Picasso - referencing the monumentality of his Large Bather, and the playful style of Girl In A Mirror. It received 77 ‘likes’, a metric most contemporary artists are familiar with tracking. Maybe republishing it here will attract a few more.